| Peak: Longs Peak Elevation: 14,255 feet Route: Notch Couloir Rating: III M3 Elevation Gain: 4,800 feet Range: Rocky Mountains Location: Rocky Mountain National Park, Colorado Date: July 1~2, 2002 Entry/Exit Point: Longs Peak Campground Ranger Station Approach: East Longs Peak Trail to Mills Glacier (about 6 miles) Guide Book: Richard Rossiter, “Rock and Ice Climbing Rocky Mountain National Park: The High Peaks,” Chockstone Press, Colorado, 1997. |

We visited Rocky Mountain National Park in July 2002 in the midst of the most devastating fire season in the Four Corners Region in recent history. Even though there were no fires within the park boundary, the smoke from neighboring fires masked the cloudless sky. The ashen cover didn’t make for good photographic background, but we were not there for taking snapshots. As much as the flora and fauna of this Rocky Mountain sanctuary may appeal to us another time, we were then focused on the main purpose of our visit—climbing Longs Peak.

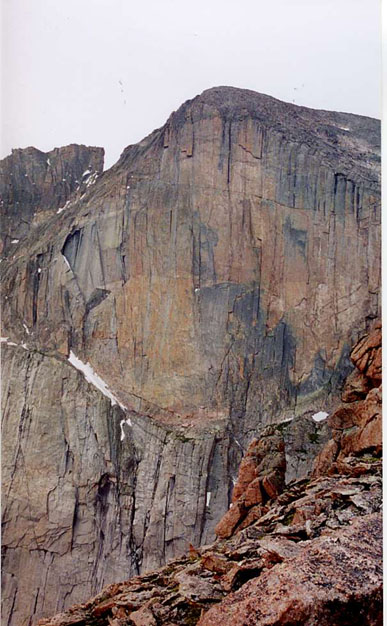

We got our first look at the massive mountain from a park road near Estes Park. Even from far away, it appeared formidable and imposing. The Notch was clearly visible despite the thick and foggy air. At 14,255 feet, Longs Peak is the highest peak in Rocky Mountain National Park and the mecca for alpine rock climbing. This monolith inspires awe in anyone with a tinge of interest in mountaineering. There are many routes to its summit, ranging from a third-class hike to the most difficult alpine climb in the country. The most famous feature on the East Face is the Diamond (see right). The easiest route up this sheer wall is the inaptly named Casual Route, rated 5.10a. Lining the southeast profile of the Diamond are the classic alpine routes, Kiener’s and the Notch Couloir. Our planned route, the Notch Couloir, stretches an impressive 1,000 feet from Broadway to the large notch 200 feet below the summit. In general, this snow and ice gully proffers good snow ascents during the summer and excellent ice climbs in the autumn. We were hoping for an alpine ice ascent, but months of dry and hot weather could already have melted out the couloir.

On July 1, we started at a very reasonable hour of 10 a.m. from Longs Peak Campground. We did not need to set off early since we planned to bivouac the first night at Chasm Lake, less than six miles away from the trailhead. The approach was enjoyable, even with our heavy packs. The trail was well-maintained all the way to the patrol cabin just below Chasm Lake. While hiking under tree cover, there were a few stream crossings on foot bridges to break up the monotony of a paced ascent. Once we emerged from the forest, a lightning warning sign and the open landscape reminded us of the danger of being caught above tree line when the afternoon thunderstorms hit. But today, the weather looked good. Sunny, pleasant, not a cloud in the sky. If not for looming East Face ahead and the granite rocks interspersed among the blooming flowers and robust shrubs, one might mistake the hike for a leisurely stroll in a Claritin commercial (see left).

On July 1, we started at a very reasonable hour of 10 a.m. from Longs Peak Campground. We did not need to set off early since we planned to bivouac the first night at Chasm Lake, less than six miles away from the trailhead. The approach was enjoyable, even with our heavy packs. The trail was well-maintained all the way to the patrol cabin just below Chasm Lake. While hiking under tree cover, there were a few stream crossings on foot bridges to break up the monotony of a paced ascent. Once we emerged from the forest, a lightning warning sign and the open landscape reminded us of the danger of being caught above tree line when the afternoon thunderstorms hit. But today, the weather looked good. Sunny, pleasant, not a cloud in the sky. If not for looming East Face ahead and the granite rocks interspersed among the blooming flowers and robust shrubs, one might mistake the hike for a leisurely stroll in a Claritin commercial (see left).

Actually, plenty of people hike this trail for leisure (which Ann would like to define as hiking without a backpack). A vast majority of our fellow hikers were headed to Chasm Lake. A number of hardier creatures had the summit in mind and some reached the top via the Keyhole Route, a non-technical ascent. This latter group had to begin a few hours before dawn to avoid the afternoon thunderstorms on their return. Thankfully, we also encountered, and passed, a few of our ilk—backpackers slouched under the growing burden that was later to provide food, shelter and security. Why “Thankfully”? Because there is no better way to boost one’s morale than seeing others toiling and suffering like, or worse than, oneself.

We rested a bit by the patrol cabin below Chasm Lake and longingly admired the alpine meadow that a nearby rock squirrel (see right) calls home. A creek meandering through the lush green carpet. Longs Peak hanging like a painting above the sky line. This is prime real estate. But we had to make the final push to our bivvy site. Trudging up some switchbacks, leaving behind the day hikers to sunbathe by Chasm Lake, taking balanced steps over the lake shore boulders, and we were there.

We rested a bit by the patrol cabin below Chasm Lake and longingly admired the alpine meadow that a nearby rock squirrel (see right) calls home. A creek meandering through the lush green carpet. Longs Peak hanging like a painting above the sky line. This is prime real estate. But we had to make the final push to our bivvy site. Trudging up some switchbacks, leaving behind the day hikers to sunbathe by Chasm Lake, taking balanced steps over the lake shore boulders, and we were there.

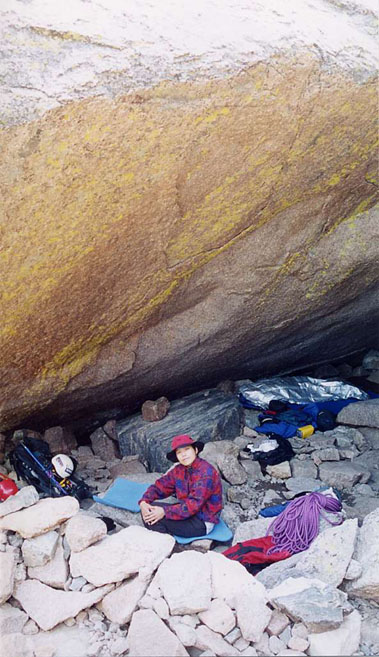

We found a spacious, well-configured alcove nicknamed “The Hilton,” just vacated by two girls who had attempted the Casual Route. A huge slab leaning against smaller boulders at a 45 degree angle forms this desirable shelter (see left). Using rocks of various sizes, previous occupants had constructed a windbreaker in the opening and laid level floors accommodating five to six people. Besides our unplanned bivvy on Mt. Whitney in 1997, we have always slept in the comfort of our Sierra Designs tent, left behind in exchange for a lighter load on this trip. We laid out our sleeping bags, ensolite pads and bivvy sacks, which are nothing more than emergency blankets sewn up as bags, and tried to rest. Sleep was hard to come by at 7 p.m., and as dusk, then night crept up, we still could not fall asleep. Marmots and pikas scampered noisily around the cave. If only they would cuddle up to me (i.e., Ann)… Finally, at 4 a.m., the watch alarm ended our foray in and out of sleep.

We found a spacious, well-configured alcove nicknamed “The Hilton,” just vacated by two girls who had attempted the Casual Route. A huge slab leaning against smaller boulders at a 45 degree angle forms this desirable shelter (see left). Using rocks of various sizes, previous occupants had constructed a windbreaker in the opening and laid level floors accommodating five to six people. Besides our unplanned bivvy on Mt. Whitney in 1997, we have always slept in the comfort of our Sierra Designs tent, left behind in exchange for a lighter load on this trip. We laid out our sleeping bags, ensolite pads and bivvy sacks, which are nothing more than emergency blankets sewn up as bags, and tried to rest. Sleep was hard to come by at 7 p.m., and as dusk, then night crept up, we still could not fall asleep. Marmots and pikas scampered noisily around the cave. If only they would cuddle up to me (i.e., Ann)… Finally, at 4 a.m., the watch alarm ended our foray in and out of sleep.

Hiking in the hours just before dawn was immensely enjoyable. The air felt refreshing and new. All was quiet except for the crunching of our boots on the rocks. The approaching twilight colored the sky a beautiful bluish gray. Soon enough, it was light and we arrived at Mills Glacier. We surveyed the East Face and saw a pair of climbers swiftly free-climbing the North Chimney on the Diagonal Wall. They had passed by our bivvy site earlier while we were having breakfast and mentioned they would attempt D7 (5.11c) on the Diamond.

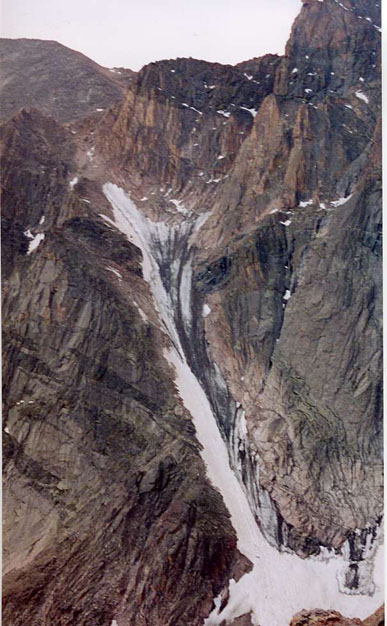

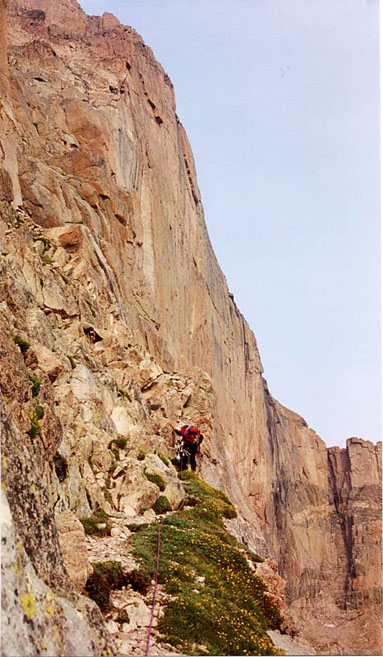

We traversed Mills Glacier and halted at the bottom of Lambs Slide, a moderately steep ramp leading to Broadway (see right), to assess climbing conditions before beginning the technical part of our ascent. The base was snowy and slushy, but, about half way up the 1,000-foot gully, alpine ice was showing. The right and center offered better ice conditions, but were predisposed to rock fall. We put on our crampons, roped up and simul-climbed along the left rock wall. After an hour or so, we were level with Broadway. We set up an anchor and belayed each other as we traversed the exposed, icy slope (see right). Getting to Broadway required every foot of our 60-meter rope and, especially when the occasional rock whished by, was quite exhilarating.

We traversed Mills Glacier and halted at the bottom of Lambs Slide, a moderately steep ramp leading to Broadway (see right), to assess climbing conditions before beginning the technical part of our ascent. The base was snowy and slushy, but, about half way up the 1,000-foot gully, alpine ice was showing. The right and center offered better ice conditions, but were predisposed to rock fall. We put on our crampons, roped up and simul-climbed along the left rock wall. After an hour or so, we were level with Broadway. We set up an anchor and belayed each other as we traversed the exposed, icy slope (see right). Getting to Broadway required every foot of our 60-meter rope and, especially when the occasional rock whished by, was quite exhilarating.

Broadway is a series of ledges above the Diagonal Wall and below the awesome face of the Diamond. By this time of the year, Broadway is for the most part free of snow, making its grassy ledges an enjoyable third-class walk (see left). There are, however, a couple of exposed step-around moves; pitons protected these areas. We quickly walked along Broadway and, before we knew it, we reached the base of the Notch Couloir. Slushy snow at the bottom of the couloir made for a slow and potentially dangerous ascent. Expecting icier conditions, we brought only ice screws and rock gear. Now, it seemed we would need some snow pickets. The snow from the couloir extended over Broadway; a fall here would result in a slide right over the edge of the Diagonal Wall and down 800 feet to Mills Glacier. We decided we would climb a couple of pitches of rock on or near Kiener’s Route and hopefully find better snow and ice conditions above.

Broadway is a series of ledges above the Diagonal Wall and below the awesome face of the Diamond. By this time of the year, Broadway is for the most part free of snow, making its grassy ledges an enjoyable third-class walk (see left). There are, however, a couple of exposed step-around moves; pitons protected these areas. We quickly walked along Broadway and, before we knew it, we reached the base of the Notch Couloir. Slushy snow at the bottom of the couloir made for a slow and potentially dangerous ascent. Expecting icier conditions, we brought only ice screws and rock gear. Now, it seemed we would need some snow pickets. The snow from the couloir extended over Broadway; a fall here would result in a slide right over the edge of the Diagonal Wall and down 800 feet to Mills Glacier. We decided we would climb a couple of pitches of rock on or near Kiener’s Route and hopefully find better snow and ice conditions above.

The first pitch of Kiener’s was easy enough. Then, we took a wrong turn and started climbing what felt like 5.9 rock, with boots no less. Errant climbers before us had left protection that led us off-route. Just as we were trying to negotiate the next pitch, we heard thunder not too far off. The sky had darkened and light snow began to fall. On the edge of the Diamond, with our ice axes sticking out of our packs, we wondered what we would do if lightning hit. We had to make a decision, and fast. By this time, we had passed the slushy part of the Notch Couloir. Here, snow conditions improved, but still softer than we would have liked. Dropping into the couloir, we carefully climbed a steep, narrow section, occasionally plunging the shaft of our tools into the snow to gain a better purchase. Although the steepest part of the couloir, this section provided the best rock protection. Moving very slowly due in part to the high altitude, we climbed up easy snow to reach the Notch. The sky had cleared and, for the moment, it seemed like the storm had passed. With ice axes and crampons stowed away, we scrambled up and north in search of the Stepladder, a 5.4 east-facing chimney that leads to the summit ridge (see right). Even with mountaineering boots, the 100-foot chimney did not feel like fifth class. The last scramble towards the summit, as is often the case, felt painfully slow, but around 5 p.m., we finally reached the summit marker (see below).

The first pitch of Kiener’s was easy enough. Then, we took a wrong turn and started climbing what felt like 5.9 rock, with boots no less. Errant climbers before us had left protection that led us off-route. Just as we were trying to negotiate the next pitch, we heard thunder not too far off. The sky had darkened and light snow began to fall. On the edge of the Diamond, with our ice axes sticking out of our packs, we wondered what we would do if lightning hit. We had to make a decision, and fast. By this time, we had passed the slushy part of the Notch Couloir. Here, snow conditions improved, but still softer than we would have liked. Dropping into the couloir, we carefully climbed a steep, narrow section, occasionally plunging the shaft of our tools into the snow to gain a better purchase. Although the steepest part of the couloir, this section provided the best rock protection. Moving very slowly due in part to the high altitude, we climbed up easy snow to reach the Notch. The sky had cleared and, for the moment, it seemed like the storm had passed. With ice axes and crampons stowed away, we scrambled up and north in search of the Stepladder, a 5.4 east-facing chimney that leads to the summit ridge (see right). Even with mountaineering boots, the 100-foot chimney did not feel like fifth class. The last scramble towards the summit, as is often the case, felt painfully slow, but around 5 p.m., we finally reached the summit marker (see below).

A couple of resident marmots greeted us at the summit, which is quite large and flat, very much like that of Mt. Whitney. We deigned to take ten minutes to rest, sign the register and snaps photos. Though we heard no more thunder, we did not want to linger exposed at 14,255 feet. We descended via the North Face, the most efficient and quickest way down the mountain. Scrambling down the northwest ridge to slabs above Chasm View, we quickly found and used the iron eyebolts to rappel 150 feet. This section could be down-climbed. However, rappelling was faster and, as it had started to drizzle, safer. We briskly descended towards the rock known as The Camel, so named for its uncanny resemblance to a kneeling camel and “surfed” the loose talus all the way down to our bivvy site.

A couple of resident marmots greeted us at the summit, which is quite large and flat, very much like that of Mt. Whitney. We deigned to take ten minutes to rest, sign the register and snaps photos. Though we heard no more thunder, we did not want to linger exposed at 14,255 feet. We descended via the North Face, the most efficient and quickest way down the mountain. Scrambling down the northwest ridge to slabs above Chasm View, we quickly found and used the iron eyebolts to rappel 150 feet. This section could be down-climbed. However, rappelling was faster and, as it had started to drizzle, safer. We briskly descended towards the rock known as The Camel, so named for its uncanny resemblance to a kneeling camel and “surfed” the loose talus all the way down to our bivvy site.

By the time we readied our packs, it was dark. Tired and with sore feet, we were not looking forward to traversing the boulder field in the dark with heavy packs. Not surprisingly, we had a hard time finding the trail down to the patrol cabin. Just as we were ready to call it a night and bivvy on the rocks, we spotted the trail. At 1 a.m., twenty hours after we started for the summit, we slumped by the car. Ann swore not to pick up the backpack for an entire year (yet we did the U-Notch just two months later) and Pedro mumbled about investing in super-lightweight gear (we still climb with the same gear). We grabbed some dinner at the only place open in all of Estes Park at this hour and plunged into a long night’s sleep.